The motivation for electric vehicles: Energy solutions

Energy solutions

After the power scheme was electrified, the focus of innovative technology shifted from the narrower engine power to the broader power system—this encompasses the motor and the battery, and especially the latter with respect to its part as an energy system.

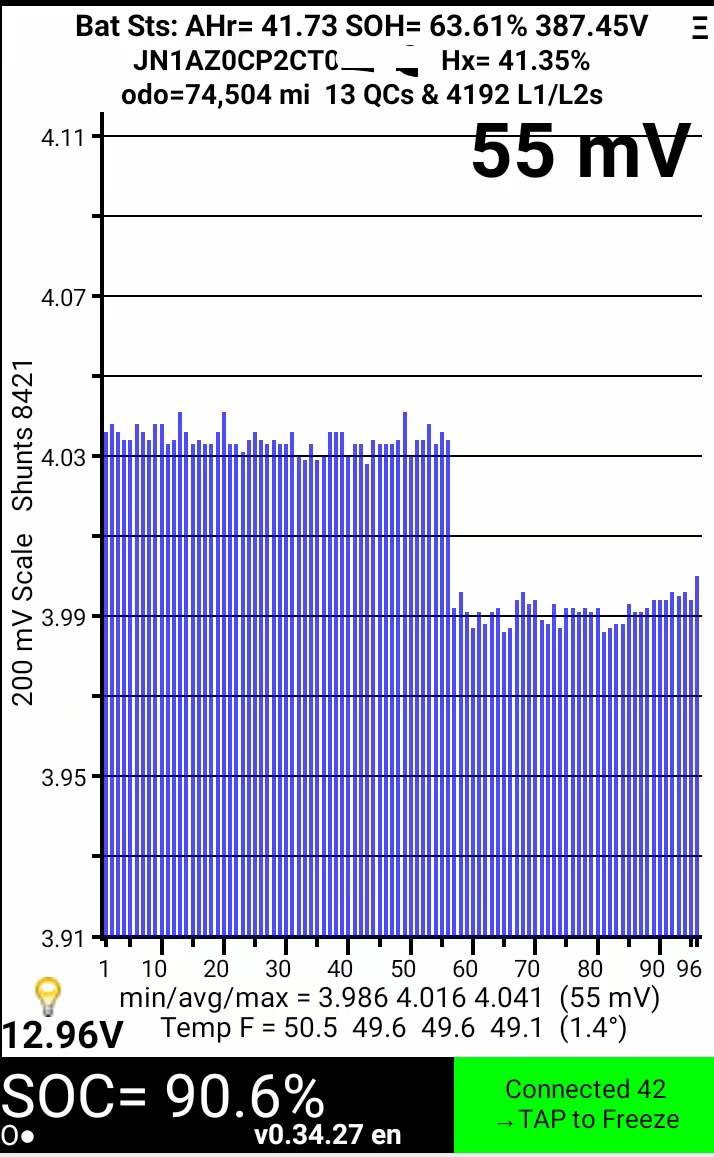

The vehicle uses lithium ion manganese oxide (LMO) batteries (which have lower chances of spontaneous combustion compared to other lithium ion batteries due to lower energy density), divided into 96 series units, each of which is composed of 4 flat, rectangular, single cells connected in parallel. These cells are air-cooled, but have no low-temperature battery heating protection. The battery management system (BMS) does not have any other temperature protection measures, only dealing with controlling charging and discharging.

So far, this may be the only electric car in mass production that utilizes natural air cooling. In terms of long-term operation, there are pros and cons. While Elon Musk has strongly "ridiculed" this model, this vehicle has never had a spontaneous combustion accident, in sharp contrast to the cars of Tesla and other car manufacturers. (One vehicle even survived a forest fire without the battery blowing up!) On the other hand, this format undoubtedly contributes to the long-term decay of the battery's capacity. While this specifically could be due to LMO's particular battery chemistry, there are also many reports of accelerated battery decay in high temperature regions (I wouldn't want to drive one of these in Phoenix during the summer). Thus, in recent years, the LEAF's cooling method has also become more active.

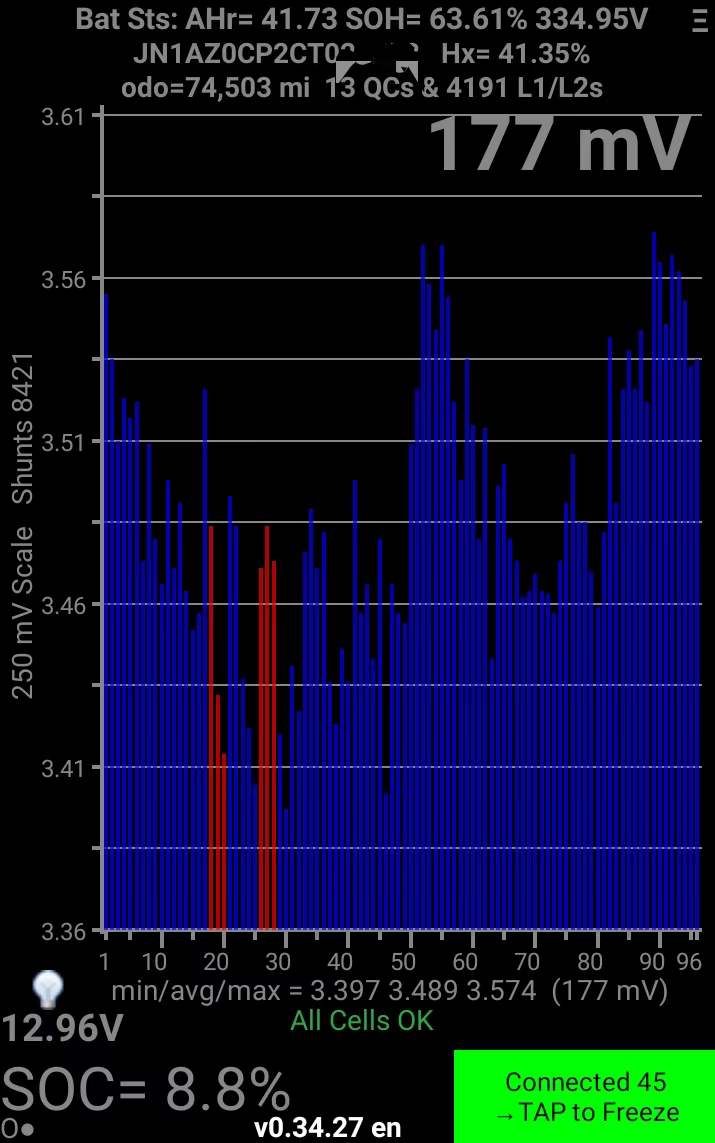

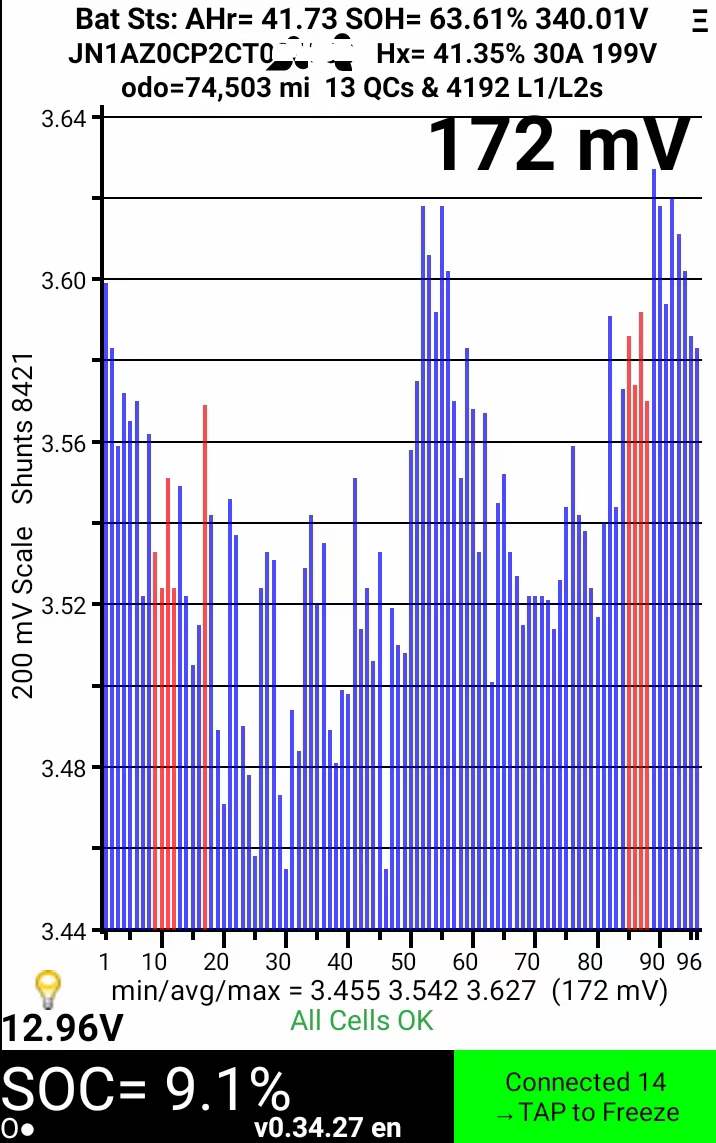

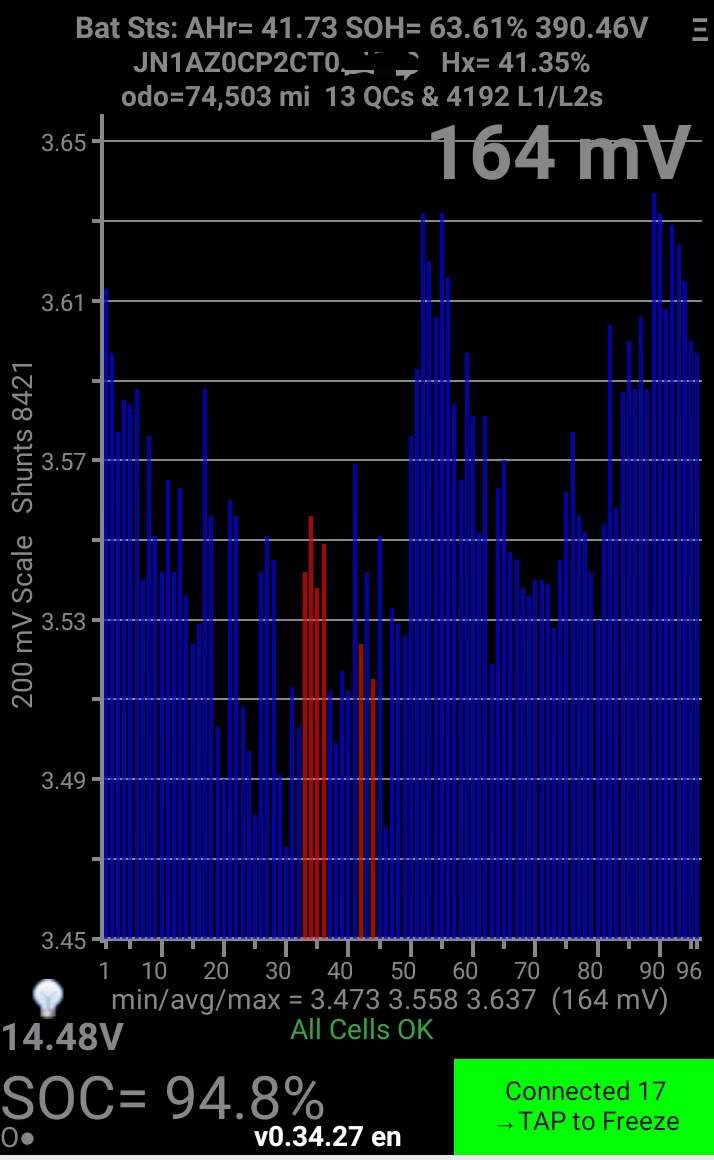

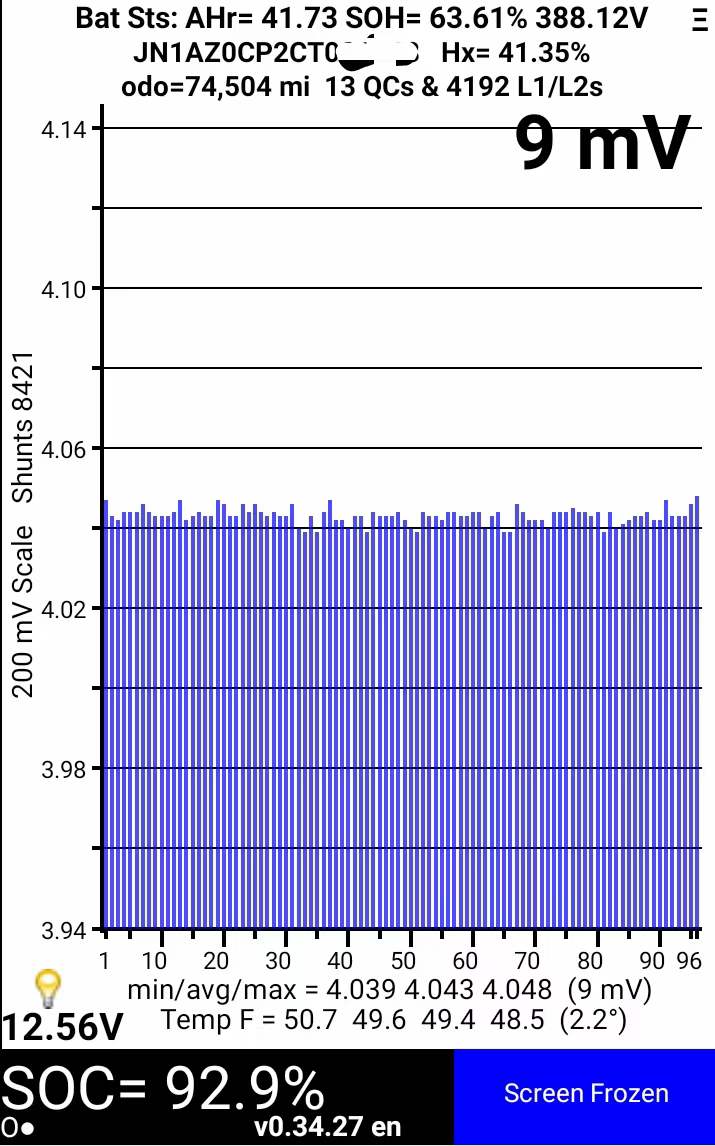

Based on the test charts shown above, it's clear that after 10 years and after almost 75,000 miles, the battery pack's capacity is about 63-65% of nominal capcity (that is, capacity out of the factory). Although this statistic exceeds the manufacturer's quality assurance requirements (the battery capacity would not be less than 70% after 5 years or 60,000 miles, whichever comes first), it is still slightly lower than this battery's expectations a decade ago—it was believed then that the capacity of these batteries, when retired and used for other purposes, would still be at 70-80% of nominal capacity.

The data show that all the battery cells are intact and the charging/discharging process is normal and stable. The cells have also all passed electrical performance tests, showing that the battery management system has been running stably and reliable for 10 years and over more than 4,000 charging and discharging cycles.

Due to the position of the market, Nissan used an LMO battery with a design capacity of 24 kWh. Although this decision was supported by lots of data (90% of passenger cars in North America have daily mileages under 40 miles or 64 kilometers), it is obvious that the main factor in this decision was to deal with the high production cost of lithium ion batteries at the time.

The vehicle itself has a single-charge range of about 100 miles (160 kilometers) and about 120 miles (192 kilometers) in the "ECO" energy-saving mode, leading to an overall energy efficiency of about 4 miles/kWh (6 kilometers/kWh). The small energy consumption is quite impressive, and most importantly, it changes little after a decade, the biggest motivator for switching power systems over to electric.

Energy efficiency is the most important detail in energy systems. This point is often overlooked.

In order to further extend battery life, capacity was attempted to be kept between 20% and 80% as much as possible, so the typical driving range under daily conditions between two successive charges is about 60-70 miles (96-112 kilometers). (However, it was found in practice that the lower limit of 20% was difficult to maintain, so the actual charging range was effectively 10% to 80%. And, by the 8th year of operation, with declining battery capacity, it made more sense to cancel the upper limit of 80% and just charge up to 100%.)

After 10 years, with battery capacity at its current state, one can get a mileage in ECO of 60-70 miles, charging from 10% to 100%. For long-term use, this can be a good estimate of long-term expectations for such car models.

Doing the math, the range decreases by about 4-5 miles (6-8 kilometers) every year.

Now herewithin lies a practical problem that electric vehicle engineers and designers must deal with in terms of battery capacity. Years past, when discussing the transition from combustion to electric, the emphasis was on the system's overall balance, including the role that software capabilities played in the process. Nowadays, however, we understand that the design of battery capacity is not just an "economic" issue, but also a "software" issue. In other words, the mechanical and electric quality of the batteries is important, but so is the software that controls energy discharge—which cells discharge first, which cells charge first, what the rate of energy release should be, etc.

Most of the problems that users of this model encounter sometimes are very much related to the "paradoxes" that arise. For example, if users want to protect the battery life by limiting the upper and lower limits of charging, they have to increase the number of charging cycles, which has a negative impact on battery life, especially for DC fast charging sans active cooling. This effect is even more prominent when the battery capacity is already rather small. Basic performance indicators were considered during the design phase's experimentation, but there were only 2,000 charge and discharge cycles, about 6 years' worth. By contrast, this very vehicle has done first and second level charging 4192 times in 10 years, with only 13 DC quick charges.

"Range anxiety" is also prevalent in the minds of other users. This is caused by poor choices by the imbalanced software. Being the first generation of electric vehicles, facing the potential of high costs, it is understandable that this vehicle would adopt a path where there is less redundancy in terms of balance. Still, reality has shown that this software's choice of balance between lifespan extension and actual use is not at the optimal setting. As the scale of batteries increases and the cost decreases, it's clear that increasing the overall battery capacity is the solution. With that, we can limit both amount of capacity charged and discharged as well as the number of charging cycles per unit time, increasing the lifespan and of course, improving overall energy efficiency.

Based on research of vehicle R&D departments over the last few years, it seems that the lower limit of battery capacity should be set at around 50-60 kWh. Popular passenger cars for the mass market should even consider aiming for slightly higher.